Overview of the cross-examination techniques

“Cross-examination” is not a good title for this part of the trial. Rather, we should call this part of the trial, “My turn to testify.” See James W. McElhaney, The Power of the Proper Mindset: During Cross-Examination, the Real Witness Is You , A.B.A. J. Apr. 2007, at 30. Cross-examination is your turn to testify directly to the jury or panel.

Once you realize that cross-examination is not an examination at all, then things will start to click. This is your chance to testify directly to the jury or panel, and the role of the witness is to validate your testimony. You are not there to get information from the witness. You are there to have the witness confirm the information you already know.

Download: Cross-examination techniques – controlling difficult witnesses on cross

The witness should play very little role while you are testifying. If you are doing this right, the witness might as well not be there. You are telling a story (testifying) and the witness is just along for the ride. You could can even look directly at the panel while you are testifying, with the witness just be making “yes,” “no,” or “I don’t know” sounds in the background.

Organizing Your Cross Examination

- Use a logical progression to reach a specific goal

- Analyze what cross-exam can accomplish and then organize the examination before the witness testifies

- Example. The goal is a concession that the car was blue

- Chapter bundles

- Be flexible

Use a logical progression to reach a specific goal

A logical progression is the optimal approach to educate the jury. Identify your goal (your main point), and then progress through your questions until your goal becomes logically true. The progression reduces the witness’s ability to evade.

Use this planned, logical progression to walk the witness to the edge of a cliff. Use the goal question to force the witness to step back, or to fall off that cliff. That is, progress to the point where the witness either must concede your goal fact, or will look foolish denying it.

You do not have to know the answer to this goal question. If you have walked the witness to the edge of that cliff, you don’t care what the answer is to the goal question. The witness will concede (you win) or look like a liar or a fool (you win). This victory will not occur unless you prepare ahead of time.

Our Lawyers Defend False Sexual Assault Allegations

Analyze what cross-exam can accomplish and then organize the cross-examination before the witness testifies

Analyze what cross-examination can accomplish and then organize the examination before the witness testifies. Create theme-based “chapters” for the cross-examination.

A chapter is a controlled inquiry into a specific area. A chapter is a sequence of questions designed to establish a goal question. A chapter advances your theory of the case one goal at a time.

- Identify your goal question.

- Review all materials to see how many different ways that you can prove the goal question. Select the witness.

- Move backwards to a more general point where the witness will agree with your question.

- Draft a series of questions leading to the goal. Start general, and use increasingly more specific questions until you reach your goal question.

- The more difficult the witness, the more general your starting point should be.

Each chapter has one main point that you will use to directly support your primary argument. If you have more than one main point, you have more than one goal question. Create separate chapters for each goal question.

The progression creates context and makes the goal fact more persuasive. By using a series of questions you support the goal fact with as much detail and as many supporting facts as you can to ensure the goal fact is believed and understood. One question is not a chapter.

Example cross-examination. The goal is a concession that the car was blue

Less persuasive cross-examination: a single fact, leading question:

- “The car was blue?”

More persuasive cross-examination: A chapter:

-

- You were standing on the corner.

- The car drove past you.

- The car drove within five feet of you.

- Nothing blocked your view from just five feet.

- It was about 1500 hours.

- It was light out.

- You got a good look at the car.

- Goal question: The car was blue

Chapter bundles

A proper explanation of an event may require several goal questions. Use one goal per chapter and then bundle the related chapters together. Start with the most general chapter first and work toward the most specific.

Example cross-examination:

- Mr. X, you’ve been convicted of a felony.

- You were convicted of robbery.

- You pled guilty in exchange for a five-year deal.

- As part of the deal you agreed to testify against Mr. Y.

Better example cross-examination:

- The police caught you while you were running away from the shoppette.

- They caught you with the .44 magnum.

- They caught you with the shoppette’s money.

- The pregnant clerk got a good look at you.

- She could identify you.

- You were caught red handed.

Goal Questions on cross-examination:

- You are an armed robber.

- You got caught red handed.

- You admitted to one fact of the robbery.

- You admitted to second fact of the robbery.

- This is relevant, because it supports how guilty Jones was, and how much Jones needed the deal.

- You were facing 15 years confinement.

- You cut a deal.

- After the deal, you were looking at no more than 5 years confinement.

- You became a cooperating witness (or “snitch”).

- That was part of the deal.

- You agreed to testify against the accused.

- You know the government will be happier with you if the accused is convicted.

Chapter 1: Goal question: You are an armed robber.

- On July 15th you needed some money.

- So you picked up your gun.

- Your gun is a .44 magnum revolver.

- Your .44 was loaded.

- You went to the shoppette.

- You pointed your loaded .44 at the clerk.

- You told her to give you the money.

- You told her you’d kill her if she didn’t.

- She was pregnant.

- She looked very scared.

- She gave you the money.

- So you didn’t kill her.

- You ran out of the shoppette.

- You are an armed robber.

Chapter 2: goal question: you got caught red handed.

Chapter 3: goal question: you were facing 15 years confinement.

Be flexible when cross-examining

Write down something that organizes your cross-exam in a way you can follow while questioning the witness.

You might put each of your chapters on its own piece of paper. As you close a chapter, line out that paper, then move to the next sheet. If the cross-examination starts to flow in another direction, feel free to go out of order on your sheets.

The Law on cross-examination

U.S. Constitution, Amendment VI: “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right . . . to be confronted with the witnesses against him . . .”

MRE 611 grants the Military Judge (hereinafter MJ) control over mode and order of interrogating witnesses and presenting evidence.

MRE 611(a)(3) allows the military judge to protect witnesses from harassment or undue embarrassment.

The scope of cross-examination is limited to the subject matter of the direct examination and matters affecting the credibility of the witness. However, if the attorney wants to ask the witness questions that are beyond that scope, the attorney can – but must now ask questions in the direct exam (non-leading) mode. MRE 611(b).

The inquiring attorney “Must have good faith basis for questions,” United States v. Pruitt , 46 M.J. 148 (C.A.A.F. 1997).

Sequence of Cross Examination

Here is a suggested sequence for your cross-examination

- Gain concessions before attacking.

- If the witness concedes every point you want from the witness. Sit down . Do not impeach.

- Show impossibility or improbability.

- Show poor perceptive skills.

- Impeach with Bias or Prejudice.

- Impeach for lack of qualifications

- Impeach with conflicting statements.

- Impeach with convictions.

- Impeach by demonstrating lies on a material point.

Tips for cross-examining difficult witnesses

- Start strong.

- End strong.

- Remember “Primacy and recency.”

- Close cross-examination with a theme chapter.

- Generally, avoid chronological order. It allows the witness to predict the cross- exam and become comfortable.

- Develop risky areas only after establishing control of the witness through safe chapters.

- If you have more than one impeachment chapter, use the cleanest chapter first.

- Reference your theme early and often.

Using Exhibits

Demonstratives are helpful in direct examination and cross examination. If you prepare well you can use your own charts/photos with an expert. If you prepare well, you can have the expert fill in the missing information in his own chart. If you are prepared, you can use contradictory theses, books, illustrations in a leading manner, after locking the witness in to their authenticity and authority.

If a witness is adverse enough to your position that you are asking leading questions, the demonstrative should also be used in a leading fashion. Great care must be taken to avoid the temptation of then asking, “So how was this used?” or something of the kind.

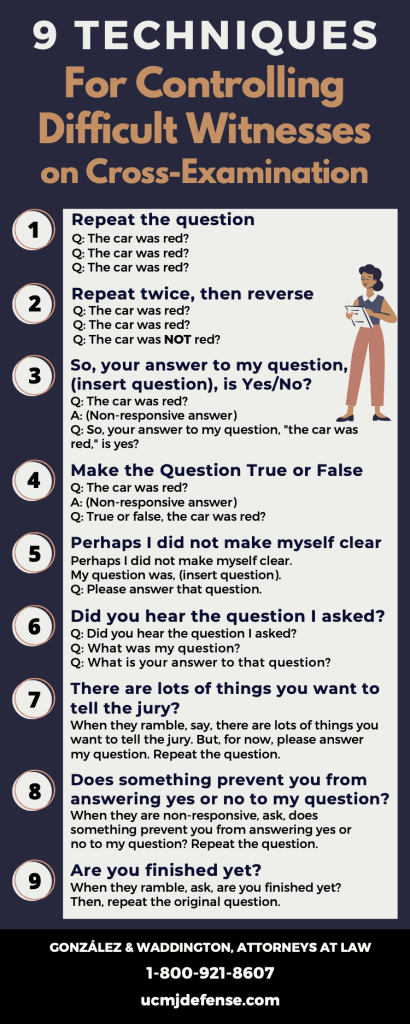

Controlling Witnesses on Cross-Examination

Leading questions are designed to keep the witness under control. Sometimes witnesses (especially experts) try to take control of the examination by answering with a narrative.

When this happens, don’t argue with the witness or plead with him or her to answer your questions with a yes or no answer. And don’t go to the judge for help. Instead, let everyone in the room know who the jerk in the room is – this witness that just won’t answer questions. The panel members or jurors want the same thing that you want – for this witness to answer the question and to not waste their time.

If the witness is rambling, try this:

Use a hand signal. Make a simple “stop” sign with your outstretched palm.

Go back to your table, look at your notes, confer with your co-counsel – anything that lets this witness know that you are going to make better use of your time than listening to her rambling. Once they are done rambling, look up and say, “You answered a different question. Here is the question that I asked you.”

If the witness won’t stay in control, try this technique.

Repeat the question. “The house was empty?”

Repeat the question again, but this time, use the person’s name: “Mr. Jones, the house was empty?”

If that does not work, ask the question in the inverse: “Mr. Jones, the house was full of people?”

Other cross-examination techniques.

“My question may have confused you. My question was not X, my question was Y.” Or, “perhaps I wasn’t clear.”

“Let me repeat the question since that is not what I asked,” and then repeat your previous question.

If the witness says, “I don’t remember,” try asking these questions (see Jim McElhaney, Evasion: Why Witnesses Do It, and How to Make Them Stop, A.B.A. J., Mar. 2010, at 26):

- Did you once know the answer to my question?

- Who did you tell?

- Who might you have talked to about this?

- Where would it be?

- What other documents might have that information?

- Where would they be?

- Who might know the information?

- Where would they be?

- If your life depended on finding this information tomorrow morning, where would you look? 10. Do you understand that if you find the answer to this question or remember what it is, you should promptly bring that to our attention?

The Evasive Witness : “I don’t remember.” “I might have . . .”

Don’t try to get better answers if the witness’ demeanor is dramatically different than on direct. If he cannot remember things on cross, but could on direct, seek as many “I can’t remember”s as possible, to areas temporally similar to areas he could remember on direct. Eventually, you can ask:

“When Major DC was asking questions about the traffic, you could remember the colors of each car in the area of the intersection, couldn’t you?”

Yes.

“But now that I am asking questions, you claim you can’t remember how close the red car was to the blue car?”

Or, after the witness evades for a while, simply ask, “Mr. Witness, is there a reason why you don’t want the jury to know the answer to that question?”

Cross-examination practice drills

For the first three drills, instruct the witness to not be a jerk. Have them answer “yes” or “no.” If they can’t answer a question “yes” or “no” because the attorney asked them a confusing question, tell the witness to just sit there until the attorney gets it right. The focus on these drills is for the attorney to get the rhythm, pace, and feel of cross- examination, not to tangle with uncooperative witnesses. Consider having the instructor serve as the witness.

Cross-examination Drill 1: Short statements.

Find any object that is in your workspace. Have the attorney describe the object, say, a coffee mug. The attorney can only use one new fact per question and needs to use a falling inflection. For the coffee mug, the attorney would say, “You are a cup. A coffee cup. White. With a handle. And you have a logo on the side. A green logo.

The symbol of a coffee company, etc.” Rotate through the attorneys, finding a new object to describe for each attorney. Have the attorneys ask at least one or two one-word questions.

As a progression, have the attorneys start with using tags, and then after two or three questions, have them work out of using tags.

Cross-examination Drill 2: Describe the action.

Have half of the class shut their eyes. Then have the witness do some physical activity – some jumping jacks, some push-ups, walk a square that is four paces on each side, do a cart-wheel (space permitting). The attorney will then cross- examine the witness on that physical activity using short statements, one new fact per question, with a falling inflection. For a witness that ran in place, the cross might be, “You pushed off with your foot. Your right foot. And brought it into the air. At the same time, you move your arm. Your left arm. You made a fist with your left hand. And pushed that fist forward. At the same time, you brought your left foot down. From the air. Onto the ground, etc.”

As a progression, have the attorneys start with using tags, and then after two or three questions, have them work out of using tags.

Cross-examination Drill 3: Describe the scene.

Have the attorney describe the room that he or she is in (or another room that they are familiar with, like a local restaurant), to include sound levels, light levels, temperature, and smell. The attorney needs to use short statements, downward inflection, and only one new fact per question. Have other attorneys describe their favorite bar at the time they usually attend it, or their church when they usually attend it, or the coffee shop they usually go to.

Cross-examination Drill 4: The runaway witness.

Modify one of the Cross-examination drills above. This time, instruct the witness to take a question and start rambling (“well, that depends on . . .). Have the attorney run through some witness control techniques (repeat the question, repeat the question using the witness’ name, state the inverse of the question).

Cross-examination Drill 5: Identifying danger words.

Modify one of the Cross-examination drills above. Instruct the witness that anytime the attorney uses a danger word (a word that is really a conclusion based on other underlying facts), the witness will stand up and say, “Gotcha!”

Cross-examination Drill 6: Case specific.

If the counsel have the basics down, have the counsel break out into teams to come up with a cross examination, based on one chapter, of one of the witnesses in US v. Archie. Bring an arguments worksheet for the counsel to use when developing the chapter.

Goal-Oriented Cross Examination

Your presumption about cross-examination is that you should not do it. That forces you to think through why you are going to ask this particular witness questions. And you need to have a good reason. You may be entering hostile territory, and you should be conducting a raid, not an invasion.

- First ask, should I cross this witness?

- Did the witness significantly damage my case?

- Is this witness important?

- What are my goals?

- Can I conduct an effective cross?

- Can I conduct a safe cross?

- Can I get the information I need from another witness?

- Is the issue that she testified about in dispute?

- Then, examine your goals for conducting this cross-examination.

- Damage this witness’ credibility.

- You could destroy the witness’ entire credibility, through story inconsistencies, by exposing bias or a reason that this witness is lying, or through prior convictions.

- You might attack just a limited subset of credibility, like the ability to perceive or remember. You are not saying that his witness is a liar; rather, you are saying this witness is mistaken.

- Elicit facts that are helpful to my case.

- Here, you have to balance the risk that you are entering hostile territory with the value that comes by getting concessions from a witness that was called by the other side.

- Under concession-based cross-examination, you elicit facts from an opposing witness because those facts carry greater weight with the jury since the jury knows the witness was not called to assist the other side.

- When eliciting concessions, the lawyer seeks agreement by an opposing witness of relevant areas of the lawyer’s own “story.”

- Elicit facts that damage the other party’s story.

- The lawyer is not attempting to tell a story, but rather attempting to unravel the one told by the opponent.

In order to identify what your goals are (and therefore, whether you should cross-examine this witness), you need to do a thorough case analysis early in the process. If you have constructed your arguments in advance using the method found in that outline, then you will see that your “especially whens” and “except whens” form the titles of your cross-examination chapters, which we will discuss below.

https://ucmjdefense

Short statements = control

- The shorter your question, the better. If you can ask a one-word question, then you have mastered cross-examination.

- Break down questions into the shortest possible question. A series of short questions provide little opportunity to equivocate or avoid the answer.

- Simplicity leaves no escape route for the witness. Simplicity builds precision.

Only one new fact per question

- If your question has multiple new facts in it, you lose control of your witness. You witness now has room to wiggle. If you inquire into more than one area in a question, which part of the question is the witness answering? The first part? The second? Both? Use of compound questions impedes an effective cross.

Only use leading questions

- The attorney asking the questions controls the witness by not allowing him/ her to elaborate on his/her answers to the fact finder.

- The attorney is testifying, rather than the witness.

- The questions may come in more “rapid-fire” fashion, giving the witness less time to think through the answer before making it and thus increasing the likelihood of a mistake (or honesty) in answering.

Occasionally break that rule by using an open-ended question

A counsel may ask open-ended questions on cross examination at any time. Doing so, of course, means a loss of control over the witness. This should almost never be used by inexperienced counsel or those not knowing the answers to their propounded questions.

Mix in open-ended questions to break up the pace of the cross-examination. For example, after a series of rapid-fire leading questions that concern a written statement, you might ask, “Where in that statement did you say X?” when you know that the witness never said X in the statement. By using that open-ended question, you create a pause in the action where everyone now has to look at the witness as the witness fumbles through the statement, only to reply, “It isn’t in the statement.”

Listen to the answers. Often those answers are helpful. They may be unexpected concessions, or contain powerful language you did not anticipate.

Use descriptive words to create a picture in the jury’s mind

- Leading Question: You saw a man lying on the side of the road?

- A better sequence using short, simple leading questions, descriptive statements, adding one new fact at a time:

- You saw a man thrown from the car.

- He was thrown from a Jeep Cherokee .

- The man was lying on the ground.

- In the dirt .

- He was lying on the side of the road.

Do not use danger words

- Danger words are any words that are not facts (nouns).

Danger words are words that are really conclusions based on other facts (drunk, hot, mad, happy). Beware of words like, “angry,” as in, “So you were angry.” Using that word gives the witness wriggle room. The witness can answer, “Well, I was a little mad, I wouldn’t say I was angry.” Rather, get the person to describe all of the facts that would lead a reasonable person to get angry (she stepped on your toe; poked you in the eye; slapped the side of your face; called you a loser), and then save the conclusion (“this witness was angry”) for your argument. - Just the facts, ma’am. Just the facts. Beware of adverbs and adjectives. Focus on noun

Representing Guilty Clients: How do defense lawyers sleep at night?

Ask safe questions

Ask safe questions– ones you know the answer to, or ones that you know the witness can only answer one way. I. Vary your pitch. J. Vary your tone. K. Vary the speed at which you speak. L. Use downward or neutral inflection.

- When someone speaks with a downward inflection, the listener is cued in that the speaker is making a statement. The listener is being told something. Not asked. Told. Notice how this sounds: “You went to the park.” There is no room to argue or answer. The listener is being told, “You went to the park.” Downward inflection = control.

- When someone speaks with a neutral inflection, the listener is cued in that the speaker has not given up control of the conversation. Notice how this sounds: “You went to the park . . . and the store . . . and the library . . . and the theater . . .” The speaker still owns the conversation. Neutral inflection = control.

- Compare that to how this sounds: “You went to the park?” You should have naturally heard an upward inflection. That was a question. The upward inflection cues the listener in that the speaker does not know the answer, and the listener should therefore respond to the speaker. The listener is given control of the conversation. Upward inflection = loss of control. M. Vary or eliminate your “hooks” or “tags” while conducting cross examination.

Court Martial Lawyers

Vary or eliminate your “hooks” or “tags” while conducting cross examination

Leading questions may be asked in a number of ways. Usually they are declarations with a hook or tag at either end of them to signal that it is a question and not a statement (although we know better!). Sometimes inflection alone allows these hooks or tags to be discarded completely.

- Some examples are:

- “Isn’t it true that…?”

- “…right?”

- “…isn’t that correct?”

- “…correct?”

- “…isn’t that right?”

- “It’s true that…”

- Often, there is neither hook nor question mark in a leading question. Ex: “You ate cereal for breakfast” Is not actually a question, but with inflection, it works just fine, and emphasizes that the lawyer is the focus of cross-exam, not the witness. If the opponent objects, repeat the “statement” exactly, and add a hook. “You ate cereal for breakfast, didn’t you?” The objection will look petty, because everyone knows what the “statement” meant.

- Your goal should be to condition the witness to the point where you don’t need to use hooks or tags. You may need to use hooks or tags at the beginning of the examination to help establish control and rhythm, and once the witness understands that you are in control, you can drop the tags. N. Avoid legalese.

Court Martial Lawyers – Alexandra González-Waddington & Michael Waddington Attorneys at Law

Avoid legalese

- If the fact finder does not understand the jargon, the witness may not, either.

Talk about losing your momentum, and maybe a good cross examination.

Real Costs of a COURT MARTIAL Conviction and Discharge

Looping

A loop begins with a single fact, leading question. The next question contains one additional fact but includes an important fact from the previous question.

Looping Cross-examination Technique

-

- Listen to any answer that’s not yes or no. Lift any useful word or phrase. Loop the useful word or phrase into the next question. Move to safety.

Example:

-

-

- The car was speeding ?

- The speeding car drove past the formation ?

- The speeding car passed the formation and hit the road guard?

-

- The double loop. Establish two desired facts using two separate single-fact, leading questions. Then combine both desired facts into one question.

Asking the “ultimate question.”

The “ultimate question” is not the same thing as “the one question too many.” The “ultimate question” is the inference that you seek to draw from your line of questioning. Don’t ask the witness to agree with your inference because the witness most likely won’t. Save the “ultimate question” or that inference for when you make your argument. Run down the list of facts that you elicited from the witness, and then, in the safety of the closing argument, tell the panel what those facts mean.

Example: through a series of short, one-fact questions, you establish that the witness is a close friend of the accused. Do NOT ask, “So you would do anything to help him out, right?” The answer will always be “I would never lie for anyone in court!”

The “one question too many” is something else entirely. You should never ask the “one question too many.” The “one question too many” is the question that blows apart the entire line of questioning you just pursued.

Terence MacCarthy, in MacCarthy on Cross-Examination , page 52, recounts this story. “You will recall the infamous ‘nose bite’ case. No less than Abraham Lincoln was the criminal defense lawyer. Initially he brought out that the witness was birdwatching. A good theme, but again, a relatively weak criminal defense theme. He was using what he had. Then Lincoln suggested to the witness that, in fact, he, the witness, had not seen the defendant bite off the poor fellow’s nose. The witness agreed.

We are told by Younger that Lincoln should then have stopped and sat down. But he continued and violated the commandment against asking the one question too many. Lincoln’s last question to the witness, the one question too many, was: ‘So if you did not see him bite the nose off, how do you know he bit it off?’ The witness answer sticks with us: ‘I saw him spit it out.’”

In fact, you should not even ask the line of questioning that leads to the “one question too many.” Because even if you don’t ask the “one question too many,” and you walk away from the witness in triumph because you did not ask the “one question too many,” what do you think will be the first question that the other side asks when she approaches the witness? Only she won’t call it the “one question too many.” She will call it “the greatest question ever.” She will ask, “How do you know he bit it off?”